An article about a solar power project our local utility is planning recently ran in one of my local papers.

An acquaintance commented on the article, advocating for the solar + battery energy storage system, saying “I am a huge environmentalist… I care deeply about nature, and I want to lessen our impacts on our planet.”

She then followed this with many paragraphs about the industrial products she has installed in her home, including thermal windows, heat pumps, water heaters, solar panels, batteries, and an EV. She described how all of this has “not yet been enough to make ours a net-zero home.”

At the end of her comment, she says “It’s not ok to be a NIMBY” and implies we must do all of these things: install solar and batteries, and buy EVs to “benefit … the symphony of life on Earth.”

She is a well-meaning human being. But she, like so many others, has fallen for industry marketing campaigns that tell us, over and over and over again, that these products will somehow “save the planet.”

I’m not sure how someone can be a “huge environmentalist” and fall for this PR, yet it has happened to many, if not most, of the people who call themselves “environmentalists”.

The following story was inspired by her comment.

Two women stood in a park, next to the fir trees, salal, and prickly rose bushes at the edge of the grass.

“I’m a huge environmentalist,” one of them was saying as two tiny newts listened nearby.

“I care deeply about nature, and I want to lessen our impacts on our planet. My husband and I implemented all the recommended energy conservation measures for our home. We got more insulation, thermal windows, heat pumps for space heating and cooling, and a heat pump water heater. We installed solar panels and battery storage. And still this hasn’t been enough to cover our winter electricity demands. We even have an electric vehicle. I don’t know what else to do.”

The other woman nodded, “I have an EV, too, and it really increased my electric bill. But we’ve got to do whatever we can to help nature, right?”

As the women kept talking, the newts looked at each other, puzzled.

“Have you ever benefitted from solar panels, Nellie?” Norris said.

“Umm, I don’t think so.” She looked sad. “I remember once I was crossing a road with my best friend Natalie and a truck carrying solar panels ran over her. I miss her a lot.”

Norris frowned, his rough skin dimpling above his eyes. He turned a darker shade of orange.

“Are you angry?” Nellie asked him.

“Heck yes,” he said. “This human is saying she’s a ‘huge environmentalist’ but I don’t see what solar panels and batteries and EVs have to do with protecting us newts.”

“Maybe they benefit other animals who aren’t newts,” Nellie suggested, trying to be helpful. She was worried Norris might turn purple.

“True. Let’s ask them!”

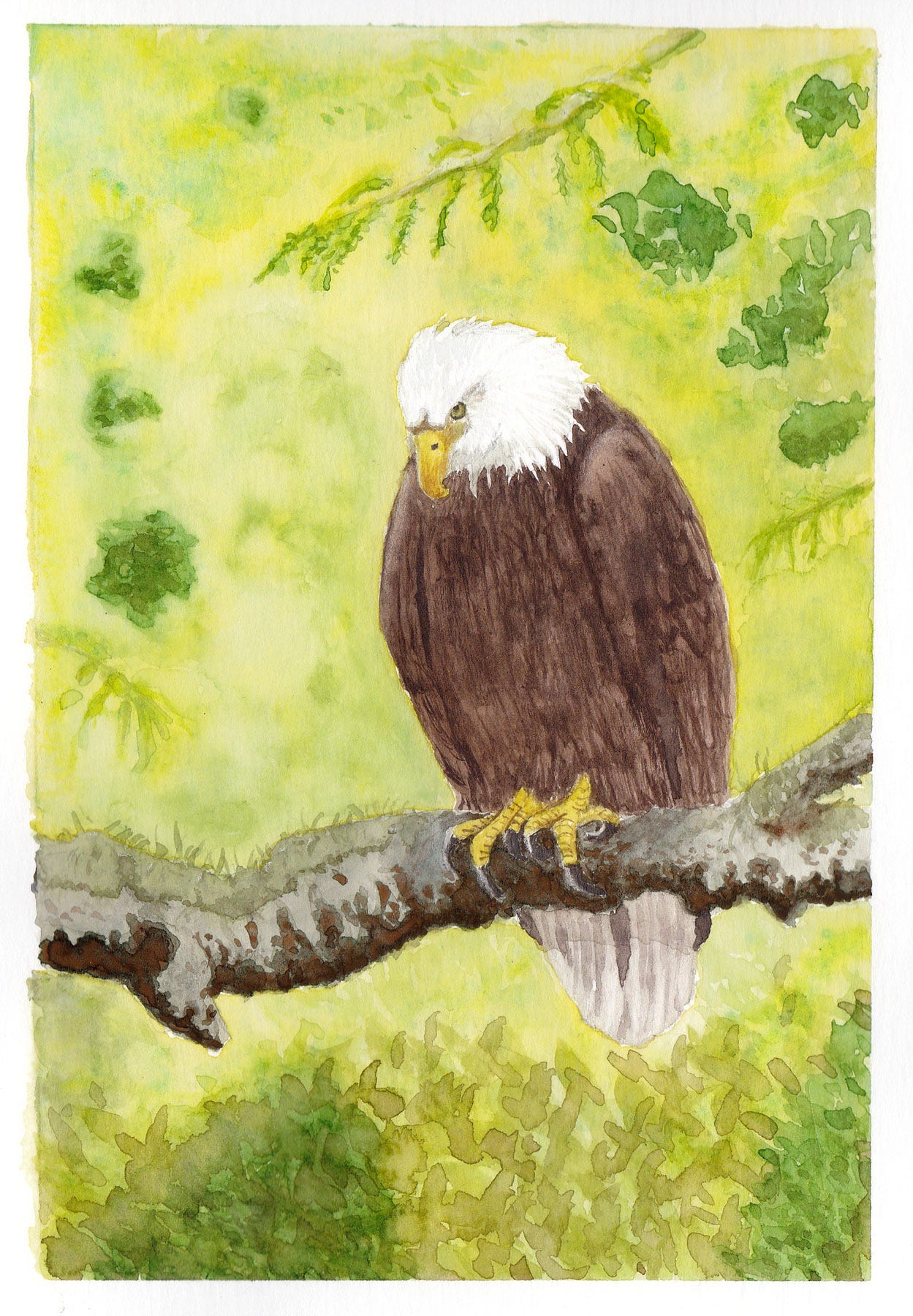

Norris looked around. He and Nellie were resting in the shade of a musty-smelling log covered in lichens and moss by the grassy area where the humans were still chatting away about “net-zero”. Norris wasn’t quite sure what “net-zero” meant so he ignored them, and looked for other animals on the grass, then in the salal behind the rotting log, and then up into the trees. He spotted a bald eagle.

“Look, there’s Ellis the eagle. Let’s ask him,” he said.

He and Nellie slowly made their way over to the bottom of the large Douglas fir tree where Ellis was hanging out on the top branch. Nellie wondered how they’d get the eagle’s attention to talk to him, but she needn’t have worried; Ellis spotted them right away.

“Hey Norris. Hey Nellie. What’s up?”

“Hey Ellis.” Norris strained his neck to look upwards to the top of the tree.

“I want to ask you: have you ever benefitted from solar panels, batteries, or EVs?”

“EVs?”

“You know, electric vehicles.”

“Oh, right, the cars.” All the animals were well acquainted with cars, as cars were so dangerous for them. Nellie had once had a long conversation with Milo the mouse about the cars that made no noise as they moved. Milo had told her how different from the loud cars the quiet cars were inside, and how the loud cars were a lot warmer for sleeping in, and had more exposed wires she could nibble on. Eventually they’d all figured out the quieter cars were the ones the humans were talking about when they said “electric vehicles”.

Ellis thought for a moment. “No, I can’t think of how I have. And now that you mention batteries, my cousin, golden eagle Sal…”

Ellis trailed off, and sat quietly staring far off into the distance.

“Sal…?” Norris prompted him gently.

“Right, Sal. Yeah so Sal recently became homeless because of batteries.”

“Oh I’m sorry to hear that, Ellis.” Nellie held back tears. She couldn’t bear it when animals lost their homes. Or plants for that matter.

“What happened?” Norris asked.

Ellis looked down at the tiny newts. “He used to live in a remote and beautiful spot over the mountain range—I visited him there once—and he told me last year that machines came and dug it all up. He overheard the humans who were driving the machines say they are digging up lithium for car batteries.”

Norris and Nellie looked at each other in alarm. They didn’t know what “lithium” was, but both had their own cousins who lived over the mountain range: tiger salamanders living in springs and creeks. What if they’d been made homeless, too?

“Where is he now?” Nellie asked Ellis.

“I don’t know. I heard from another bald eagle he’d stopped by to visit as he searched for a new home but I haven’t heard anything since.”

All three sat quietly for a few moments.

A creak and then a loud grunt broke the silence. Doug, the Douglas fir Ellis was sitting on, cleared his throat.

“Can I chime in here?” Doug asked.

“Of course,” Norris said.

Doug spoke slowly, as old trees are wont to do.

“I just wanted to say I’ve lost many relatives to solar panels and mines. Just in the last 20 years, 3.5 million acres of forest have been cut down for mines. That’s 35 billion of my tree relatives murdered!”

Nellie couldn’t help herself. She began to cry a little.

“How do you know, Doug?”

“The funginet.”

Nellie knew the funginet was a great source of information for trees. She envied their ability to communicate over such large areas.

“What’s a mine?” asked Norris.

Ellis had seen many mines in his travels around the Pacific Northwest, particularly to the north. He explained, “It’s like what the humans are doing where Sal used to live. They dig up huge piles of rock and dirt with big machines and move it around. The noise is horrendous; it scares us all. And there’s no trees or plants left after they’re done. The humans find stuff in the rock they like to make things with. Maybe it’s a bit like finding a tasty herring in the stomach of a salmon.” He looked out over the nearby bay, thinking about fish.

Doug cleared his throat again. His deeply creviced bark creaked just a bit. “They use the stuff they dig up from under us trees to build things like solar panels. But of course they have to kill all the trees and bushes and wildflowers first to get at it. They burn some of those trees in factories where they make the panels. At least, that’s what I’ve heard.” Some sap weeped from his trunk, dripping on the ground next to Norris. It smelled sweet and citrusy.

Ellis looked down at the newts again. “And then when they have finished building things with all the stuff they mine, the humans cut down more trees and use their dead bodies—sorry Doug—to carry these long lines to places where they put the panels. And sometimes they put hard metal boxes right next to the panels. Those are the batteries. I watched them install a few and overheard the humans talking about the boxes. I’ve been seeing a lot more of these lines and panels and battery boxes popping up all over when I travel. I don’t know what it’s all for, but usually, a lot of trees are killed when the humans do all this.”

“You’ve seen this yourself?” asked Norris. He’d never seen anything like it. It sounded a bit far fetched.

Nellie looked at Norris, and said “Remember Nora?” He nodded. “She used to live in the bay over that hill, next to what I think might be a mine. She said big machines came every day to scoop out tons of rock and gravel. She heard from her grandmother Natalie that there used to be lots of trees with lovely moss and wet logs and puddles to live in there, but now it’s all gone and it’s just machines scooping out rock.”

Ellis knew that mine well. It was small in comparison to some he’d seen.

“I think there are some sheep who live in a field covered in solar panels a few miles away. You could ask them what they think of the panels,” he suggested to the newts.

Norris groaned. “We can’t get over there, Ellis. Remember how slowly we newts walk; it takes us weeks just to go a mile or two.”

“I’ll go,” Ellis said.

“The sheep won’t talk to you,” Nellie said. “They’re scared of you.”

“I’ll figure it out,” and off he flew, his massive wings momentarily creating a shadow over Nellie’s eyes. She blinked, wondering what it would be like to be able to fly.

“I’m getting too hot,” said Norris. The newts had been standing in the sunshine talking to Doug and Ellis for quite a while.

“Walk around my trunk to the northeast,” said Doug. “I have a dark mossy spot over there for you in between a couple of my roots.”

By the time the newts got to the mossy shady spot, Ellis was back.

“That was fast,” creaked Doug as Ellis landed on a big branch on the northeast side of Doug, so he could see the newts below.

“How’d it go?” asked Norris.

“Well, I couldn’t get near the sheep, they hid under the solar panels. So I asked Callie to talk to the sheep…”

“Callie?” Norris and Nellie asked simultaneously.

“The Canada goose. She couldn’t get near the sheep either. They’re a flighty bunch. So Callie asked Gertie—the garter snake—what it’s like to live by the solar panels.”

“And?” Norris, Nellie, and Doug were all eager to hear.

“Gertie is not a fan. For one thing, some trees were killed—sorry Doug—to make way for the panels, and also for the lines from the panels to wherever the lines go. Gertie liked the trees and now they’re gone. And she said that once there was a hailstorm that broke some of the panels. She wasn’t living there at the time, but she moved over there shortly after the storm and she said the snails who lived under the broken panels didn’t taste right. She prefers the snails she finds in the woods.”

Doug groaned. A few of his top branches swayed a bit. “I’ve heard about the bad taste from mushrooms and trees on the funginet. They say the Earth and the water near the mines tastes bad, too.”

“And there’s more,” said Ellis. “Callie told me she had a cousin, Mal…”

“Cousin Sal?” Nellie said.

“No, cousin Mal, the mallard duck. Mal tried to land on the solar panels thinking they were a lake. They look a bit like water in the sunshine.”

“What happened to her?” Nellie didn’t really want to hear the answer.

“She broke a wing, and didn’t last too long.” Ellis thought to himself, “And one of my eagle friends probably ate her,” but he didn’t say that. He didn’t want to upset Nellie even more.

They all fell silent.

Norris eventually spoke. “So far, it seems the only ones the solar panels benefit are the sheep, who can hide from eagles under the panels.”

Nellie snuggled deeper into the soft moss living around Doug’s roots, feeling quite tired and demoralized by the conversation.

Suddenly, there was a rustling sound in the bushes behind Doug. Nellie and Norris immediately hid underneath one of Doug’s big roots. A Western pond turtle crawled out from beneath the salal and plopped down next to Doug.

Doug creaked, and swayed a couple of branches; just a bit so as not to scare the turtle. “Hello,” he said. The deep sonorous sound of his voice was just right for the turtle, who didn’t retract his head or any of his legs, and didn’t seem afraid.

“Hello,” the turtle said. “Who are you?”

“I’m Doug. Who are you?”

“I’m Toby. I came from the small pond behind the bushes.” He nodded his head back towards the bushes to indicate where the pond was. “I came over to see the sunset.”

Ellis, who was staying quiet so as not to frighten Toby into his shell, looked towards the Western horizon. Yes, the sun would be setting soon. The time had flown by.

Norris and Nellie stayed huddled below Doug’s root.

Nellie whispered, “Do you think he’d eat us Norris?”

“He might,” Norris whispered back. “But I really want to ask him about solar panels and EVs.”

Doug could hear the newts whispering through his delicate fine roots just below the surface of the soil.

He said, “So Toby, do you know anything about solar panels or EVs? I’ve been chatting with some friends recently and we’re wondering if they benefit…well, anyone.” He was going to say “newts” but didn’t want to give away Norris and Nellie’s presence nearby.

“Oh tree, do I ever,” Toby said, nodding his head so vigorously his whole shell was shaking.

Norris wanted to sneak out to listen more closely but Nellie put one of her toes on one of his toes to keep him still.

“Tell me more,” said Doug.

“It’s a long story,” Toby said, worried he might go on too long for Doug.

Doug shook a few of his needles to indicate he thoroughly enjoyed long stories.

“Okay then,” said Toby, and proceeded to tell his story.

“Last year, I made friends with a desert tortoise. How on Earth did I meet a desert tortoise all the way up here in the Pacific Northwest? you might be asking.” Doug shook his needles again, and Nellie and Norris looked at each other with surprise, while Ellis stared miles away to the south thinking about what a long flight it was to the desert.

“Well, the desert tortoise I met—Dolly—was one of hundreds of desert tortoises who were being evicted from their homes so the humans could install solar panels. A few of the humans dug up Dolly and some of the other tortoises from their burrows, put them in boxes, and carted them off to where another desert tortoise colony lived. They left behind most of the baby tortoises, so the mothers, including Dolly, were distraught. She cried and cried as the humans took them all away in their big machines.” Toby looked sad. A tear rolled slowly from one of his beautiful brown and yellow eyes.

Doug shed a few needles onto Toby’s carapace in sympathy.

Toby composed himself and continued. “They took all the boxes out except for Dolly’s box and let the tortoises go. Dolly said she figured they wouldn’t last long.”

“Why not?” Doug asked.

“She’d heard about these evictions from tortoises who had been moved into where her colony lived a few years ago. The new tortoises didn’t have burrows so they were vulnerable. Some got eaten by badgers before they could build new burrows. And some of the tortoises died from home sickness. A few missed their home so much they tried to go back. But the humans built a big fence around their old home so they couldn’t get back. And anyway, even if they could have, the humans removed everything inside the fence before they put up the solar panels. One of the tortoises Dolly talked to said everything alive is scraped from the ground, including the soil. There’s no one left. All their babies died too.”

Another tear rolled down Toby’s cheek.

“So how did Dolly get all the way here?” Doug asked after a few moments.

“One of the humans put her box into another car machine and moved her here. It took a long time to get here, even on tortoise time. She overheard the human talking about how they had to move the tortoises because tortoises are ‘endangered’ but that solar panels are more important than tortoises because the humans need the solar panels to charge their electric vehicles. I don’t even know what that means, but if desert tortoises are losing their homes…”

Toby looked despondent.

“How did you come to meet Dolly, then?” Doug wanted to hear the end of the story.

“The human took Dolly out of the box and put her in a little enclosure with some sand. Dolly used her arms to dig the sand and make a big enough pile she was able to escape the enclosure. She was crawling through the woods when I met her.”

“She must have been so confused,” Doug said sadly.

“Oh, she was,” Toby continued. “She was wet and cold and couldn’t find anything to eat. She said she liked to eat cacti and there isn’t much of that around here. I offered her some grasshoppers and cattail roots but she wasn’t interested.”

“What happened to her?”

“We hung out for a few days. She eventually tried to eat some salamander eggs, but she was unhappy and missed home. She wandered off one morning, and I haven’t seen her since.”

Norris and Nellie looked at each other. They didn’t like that Toby was eating salamander eggs, but felt terrible for Dolly. Toby’s story indicated solar panels weren’t doing anyone except humans much good at all.

“I really liked her,” Toby said. “We were very different but she had a beautiful shell.”

He sighed. “I guess we missed the sunset. I’m going to head back to the pond now.” He slowly turned and shambled off under the salal bushes back the way he’d come.

Norris, Nellie and Doug had indeed missed most of the sunset; Norris and Nellie too intent on hiding from Toby, and Doug too intent on listening to his story. Ellis, however, had a perfect view of the sunset from his spot in Doug’s branches, and even now the orange and pink glow in the sky was reflecting from his bright white head feathers.

Everyone was tired. They agreed to call it a night and see what happened in the morning. Nellie and Norris shared a few spiders for dinner, snuggled deep into the moss around Doug’s roots and fell asleep. Ellis, always a light sleeper, watched the last of the color drain from the sky as the bats flitted here and there over the park—now empty of humans—catching moths and mosquitoes by the dozens. Doug listened for news on the funginet, his smallest branches swaying in the light breeze that picked up as the stars came out. All was quiet.

~~~

The next morning, Norris and Nellie woke up as the sun’s light began to fill the sky.

“Good morning” rumbled Doug, his morning voice low and soothing.

“Morning, Doug,” the newts said in unison. “Where’s Ellis?”

“He probably went off to look for breakfast,” said Doug.

The newts crawled slowly around Doug’s base, looking for worms, their favorite food in the mornings. Norris took a bath in a tiny puddle in one of Doug’s large roots, hidden from view by the verdant fronds of a sword fern and moss.

Ellis returned, massive wings outstretched as he landed, his large talons glinting in the rising sun. His beak was bright red, stained with blood. Nellie was glad she was too tiny for him to bother eating.

Ellis sat on Doug’s highest branch scanning the area. A few humans were walking by the park along the sidewalk; an elderly couple were sitting on one of the benches having coffee. A small white poodle on a leash sniffed around the ground by their feet. If Ellis hadn’t been full already, he might have wished the poodle would escape… but he was indeed full. And he had a thought to share.

“Hi Norris, Nellie. Hi Doug,” he said.

“Hi,” they all said in return.

“I was just having breakfast. A deer was hit by a car overnight, and a human dragged the deer into the trees beside the road.”

They were all silent for a moment.

“Anyway,” Ellis continued, “as I was eating I thought about how all kinds of cars hit deer. It doesn’t make a difference what kind of car it is. They all hit deer. And rabbits. And sometimes even raccoons.” He’d seen rabbits, raccoons, deer and even eagles who’d all been hit by cars. And he’d seen plenty of both loud and quiet cars hitting them, so he knew what he was talking about.

Norris and Nellie hated cars. They’d both lost many relatives to cars. Roads criss-crossed their habitat, making it a treacherous journey from the ponds and few remaining wetlands where they laid their eggs, to where they lived in the woods between breeding seasons. They were both traumatized from seeing so many of their friends and relatives squashed flat on the roads by these speeding machines. The quiet cars were worse, because the newts didn’t hear them coming until it was far too late.

Nellie looked up at Ellis, perched high above her. “So what you’re saying is that electric vehicles are just as bad as any other kind of car, right?”

“Yes; that’s my opinion.” Ellis looked fierce as he said this. Then again, he always looked fierce.

“But the humans seemed insistent that EVs are part of being a ‘huge environmentalist’. I don’t get it.” Norris was unhappy. He’d been determined to figure out how solar panels, batteries, and EVs would help the newts and he was running up against a wall here.

“Maybe it’s about something else entirely,” Doug suggested.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, I’ve noticed a significant change in the air quality over the past few decades.” Doug was 250 years old, one of the few old-growth trees left in the region. He was one of the lucky ones; most of the trees he’d grown up with were killed over a century ago. He was now surrounded by trees much younger than him.

He continued, “Back when I was just a sapling there was a lot less pollution in the air. There was also a lot less carbon.”

“Carbon?” asked Ellis.

Doug was an expert chemist, as all trees are. “Carbon’s one of the elements I build my body with. You probably do, too Ellis, but perhaps in different ways. My wood is made out of carbon. I breathe in carbon dioxide, combine it with water from the Earth and sun from the sky to extract the carbon to build my body, and release the leftover oxygen back into the air. You three and all the other animals then breathe in the oxygen.”

“Wow,” said Nellie. “I had no idea.”

She sat quietly for a few minutes, breathing. She realized she and Doug were sharing the same breaths.

“But what does that have to do with cars?” she asked.

“When some cars drive by, I can sense the carbon dioxide—CO2, for short—coming out of them. And other cars come by, and there’s no CO2.”

Nellie and Norris weren’t getting it. Neither was Ellis. None of them knew nearly as much about chemistry as Doug.

Doug explained, slowly. “More CO2 from all these cars has been changing the climate. I can feel it. 250 years ago, there was a lot less CO2 in the air, and the climate was different.”

“But don’t you like more CO2?” Norris asked. “That’s what you breathe to build your body.”

“A little more CO2 is okay,” Doug said. “But a lot more CO2 can screw up my nitrogen uptake. And if it changes the weather, that can make life more difficult for me and my tree and plant friends. There’s always a lot of chatter on the funginet about this issue.”

Ellis was getting a bit frustrated. He still didn’t understand what this had to do with cars, and EVs in particular.

“Bring it back to the cars, Doug,” he said.

“Right, so some of the cars don’t leave CO2 behind. They leave other things behind—for instance, lots of tiny bits of plastic, like all cars do. The plastic gets into my stomata and my roots and is really annoying and toxic.” He shook his branches, just thinking about it. “But no CO2. I think those are the electric vehicles the humans are raving about. The other, louder cars must use lots of carbon if they are leaving CO2 behind.”

Norris was finally starting to understand, and he didn’t like it. To him it made no difference how much CO2 a car left behind when the car was killing his friends and relatives. So what if the CO2 from the cars was changing the climate?

“Every kind of car kills newts… and deer and rabbits and raccoons,” he said. “So, I still don’t understand how an electric car means a human cares about nature, when their cars are killing everyone, and all the roads they build to put the cars on make it so difficult and dangerous for us newts to get anywhere.”

Nellie had been thinking hard. She liked to try to see the big picture, and the big picture was unsettling her.

“So, I’m going to see if I can summarize what we’ve learned,” she said. “We know that humans think that solar panels and batteries and EVs make them ‘huge environmentalists’.”

Everyone nodded.

“And we know that no one other than humans really likes solar panels, whether they are nearby here or far away in the desert.”

More nodding.

“And we know that mining for batteries is destroying Sal’s old home beyond the mountains, and that murdered trees are used to make solar panels and those poles for the lines from the solar panels.”

Doug reminded her, “And don’t forget about my 35 billion relatives murdered for mines, everywhere.”

“Right,” Nellie said. She knew that 35 billion trees was a lot of trees but couldn’t really wrap her brain around a number that large. “The humans kill all the trees and then tear up the Earth to get the materials to make things like solar panels and batteries and EVs.”

Doug had an idea. “Maybe the solar panels and batteries don’t leave behind any CO2, just like the EVs don’t,” he said. “I’ll ask the trees who live next to the solar panels and batteries over the hill, just give me a moment.”

Nellie and Norris and Ellis waited. They knew the funginet was large, but slow. It operated on fungi and tree time. Norris snacked on more worms while Ellis scanned the horizon and Nelli watched the sunlight dancing between Doug’s needles.

“Got an answer, everyone,” Doug said finally, after a long period of quiet. “The trees over the hill don’t sense any CO2 from the solar panels and batteries.”

Ellis said, “Well then, you may be right Doug. Maybe for the humans it’s all about the CO2.”

Nellie was confused. “Okay, Doug has told us that the CO2 is changing the climate, and he should know. He’s old and wise.”

Doug blushed, a response invisible to the newts and eagle. Blushing for a tree is a rush of hormones in the cambium, beneath the bark.

“So maybe the humans don’t want the climate to change,” Nellie continued. “But if the humans have to destroy so much nature to make solar panels and batteries and EVs, how does that help anyone? Murdering trees and digging up the Earth and making golden eagles and desert tortoises homeless and squashing newts on the road is bad for everyone, including the humans.”

Nellie understood, as all wild plants and animals do, the intricate connections in the web of life. She knew instinctively that when nature is destroyed, the web of life breaks, and when that happens, that’s the end for everyone, human and non-human alike.

“I think these humans are very confused,” said Doug. “The humans don’t want the climate to change because of CO2, and they think that by destroying the Earth to make solar panels and batteries and EVs, they’ll make less CO2. But when they destroy the Earth, they destroy all of us; the trees, the eagles, the newts, the pond turtles, the desert tortoises, and everyone else.”

Doug was getting quite agitated, creaking and groaning as he spoke.

“And, going back to the carbon that builds my body—when they murder the trees to build their machines, they’re killing the very beings who remove the CO2 from the air so we can use the carbon to build our bodies and breathe out the oxygen that everyone else breathes in. It makes no sense. With all this nature destruction, eventually they’ll destroy themselves, too.”

Ellis sighed. Norris and Nellie felt sad. They all knew Doug was right. The wise old Douglas fir was right.

“So, what do we do?” asked Nellie.

“There’s nothing we can do,” said Doug, weeping a few more drops of sap.

Norris shook his head. “We’re wild,” he said, proudly, lifting his head and tail high, his orange underbelly glowing. “That’s what we do. We just keep on being wild.”

Nellie nodded, and ate a spider.

Ellis stretched his wings, looked off into the distance and let out a high-pitched screech.

Doug stood tall, and swayed a little in the breeze.

Ellis is sad.

And so am I.

I love this. It would make a great animated feature.